1. Introduction and Overview

The Chinese economy has grown rapidly over the past twenty-five years, a period of liberal economic reform involving the (at least partial) privatization of much state-owned industry, the encouragement of private entrepreneurship, and the removal of price controls, protectionist trade policies, and burdensome regulation. Indeed, most point to China’s market-oriented reforms and more flexible state economic policies as the primary driver of its “economic miracle.” In this regard, what is presently being observed in China has some noteworthy parallels with the experience of the “Asian Tigers” in the postwar period and Eastern Europe during its transition period in the 1990s. Liberalization and privatization have profoundly impacted Chinese industry at virtually all levels, including, perhaps somewhat unusually, traditional folk art.

Especially noteworthy in this regard is the market for tiehua, an industrial art form identified with the city of Wuhu in Anhui Province. The tiehua industry was collectivized in the late 1950s, and it has changed drastically over the past generation: Wuhu Tiehua, the state monopoly that resulted from collectivization, has floundered and undergone multiple restructurings while several new firms have entered the market. Indeed, the marketization of tiehua has become a significant local issue centered on market structure and the ownership structure of tiehua firms. What is perhaps most interesting, however, is just how closely the characteristics of the tiehua market before and after economic liberalization align with basic economic theory; evidence suggests that deregulation and privatization have given rise to a considerably more innovative, efficient, and competitive industry. In this regard, the tiehua market represents a textbook case study in industrial organization.

This paper documents and analyzes the changes in the tiehua industry over the past quarter century. In doing so, we make three contributions: First, and as already noted, this period in the tiehua industry is a textbook example of basic economic theory and industrial organization. For economics and business teachers and students, the tiehua industry presents a clear connection between business ownership, market structure, and firm performance. Second, although business in China has attracted much attention, the field of business history is not particularly robust; this paper will add to a growing body of academic research on Chinese business history. Similarly, while both Chinese and English news media have reported on the success of China’s economy, particularly stories of joint ventures and state-owned enterprises in Beijing and Shanghai, relatively smaller businesses in relatively smaller cities such as Wuhu have received little attention. Indeed, privatization has become a significant local issue centering on market structure and the ownership structure of the various tiehua firms. Finally, tiehua represents an opportunity to document the potential frictions arising with traditional artisans operating in a modern market economy.

The organization of the remainder of the paper is as follows: The following section briefly outlines the broad evolution of China’s business environment since circa 1990. Section 3 details the history of the tiehua industry under the communists. Section 4 is our main narrative: an analysis of how privatization has impacted the tiehua industry and will impact it going forward, followed by concluding remarks and an appendix.

2. China’s Business Environment Since 1990

The genesis of China’s broad economic liberalization dates to the economic reform of 1978 and the ensuing decollectivization of its agricultural sector in the late 1970s and the creation of rural community enterprises in the 1980s (Zafar 2010). When industrial liberalization began broadly in the 1990s, reforms generally took two forms: gaizhi, partial or full privatization, and zhiqi fenkai, the separation of the government from business operations; the initial experience of Wuhu Tiehua falls into the latter category. The pace of liberalization was initially slow, with reforms implemented at an incremental, almost idiosyncratic rate, seemingly lacking a coherent design (McMillan and Naughton 1992). And all the while, new, smaller, and fully private firms were being created and entering markets of all sorts.

The seemingly ad hoc nature of China’s liberalization programs makes systematically documenting China’s recent business history a tall order, especially with regard to small and mid-sized firms, and no doubt goes a long way in explaining the relative dearth of literature in this area.

Extant research primarily focuses on the macroeconomic aspects of China’s state-owned enterprise reforms. Chang-Tai Hsieh and Zheng Song (2015), for example, attempt to explain the large jump observed in labor productivity in China during the 2000s as a result of economic liberalization. Other studies are concerned with the frequently complex role of local governments before and after the privatization process (Walder 1995, 1998; Palepu, Khanna, and Vargas 2005). There have been relatively few attempts to focus on smaller, local state-owned firms such as Wuhu Tiehua from a microeconomic perspective.

A few generalities, however, can be made. First, China’s reform process was far from popular. The initial reorganizing and privatizing of state-owned firms frequently resulted in mass layoffs and was often met with resistance from company managers, many of whom were Communist Party apparatchiks; Wuhu Tiehua is a typical firm in this regard (Gao 2015; Li et al. 2015). Second, most state-owned firms were fundamentally inefficient. Due to privatization and restructuring, the number of state-owned firms in China has fallen by approximately two-thirds in the past generation (Knowledge at Wharton 2006). Many of these have since failed, which the Chinese authorities are more than willing to let happen; Wuhu Tiehua is also typical here. Moreover, many of the roughly 40% of remaining fully or partially state-owned firms in China consistently face losses. Finally, the involvement of the Chinese government in the Chinese economy remains ever-present. Communist Party officials are often shareholders in newly reformed firms, and Chinese industry remains heavily regulated by Western standards.

China’s transition period was, economically speaking, an almost unqualified success, on net. Since 1990, thousands of state-owned firms were reorganized and millions of private firms have been launched (Haveman et al. 2017). The output produced by private enterprise now comprises the bulk of Chinese economic activity as measured by gross domestic product (Atherton and Newman 2017). Chinese economic growth has averaged over 9% per year since 1990, and the Chinese economy has not experienced a recession since 1978. All of this lies in sharp contrast with the performance of the economies of Central and Eastern Europe during their transition period in the 1990s, where economic volatility and uncertainty was the rule (Coricelli and Ianchovichina 2004).

3. The Tiehua Market to 1990

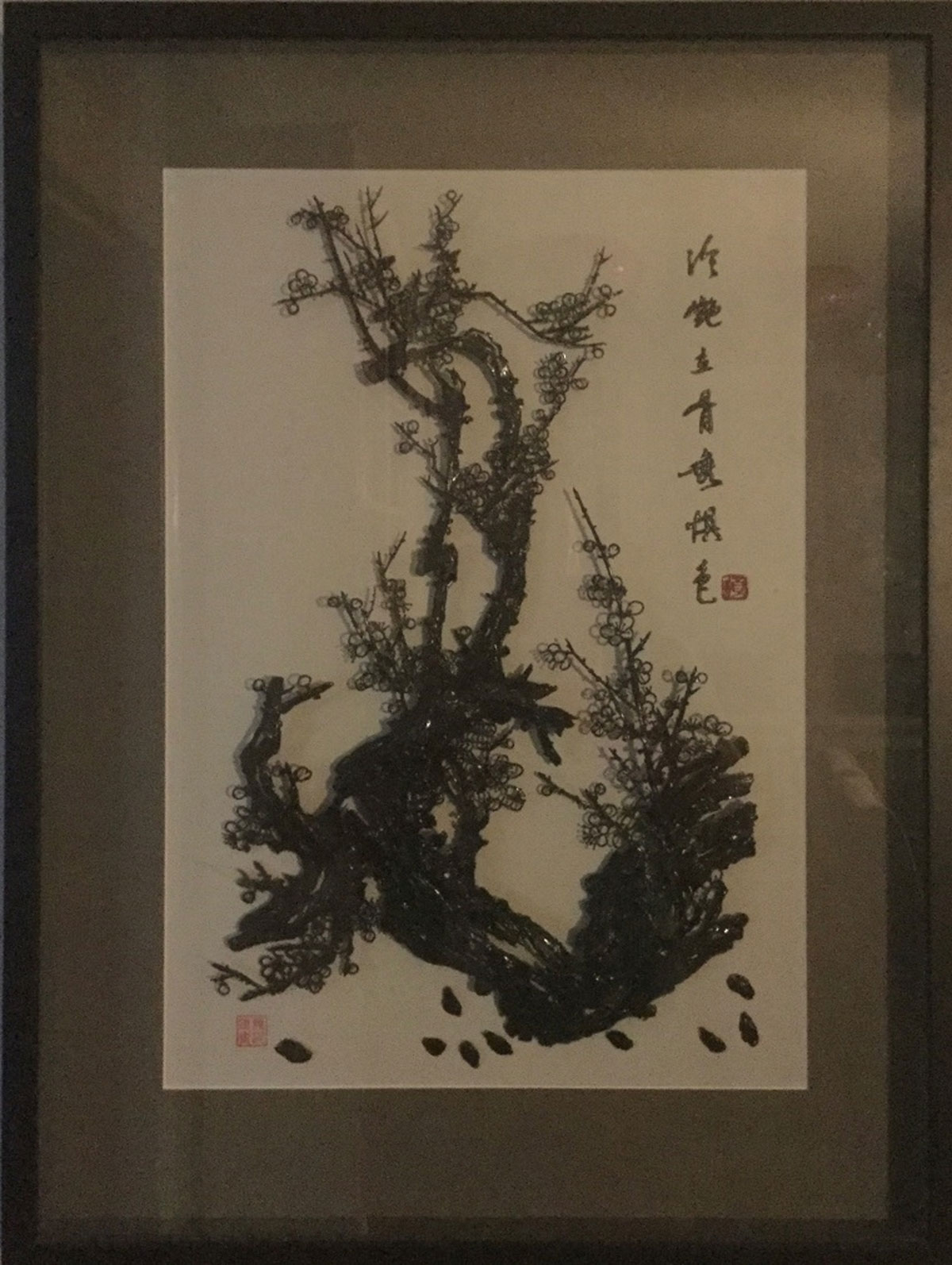

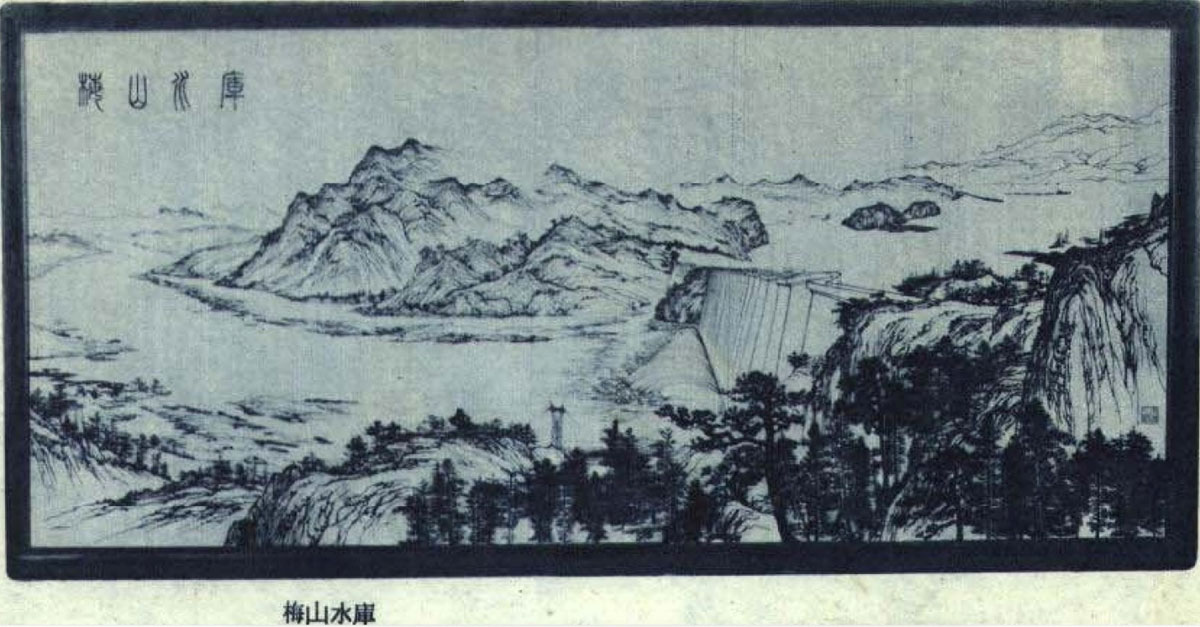

With origins dating to the seventeenth century, tiehua, or wrought iron painting, is a relatively unknown art form. Using traditional black-and-white brush paintings as rough models, tiehua artisans forge intricate quasi-three-dimensional representations of landscapes, birds and other fauna, and other subject matter (see Figures 1 and 2). The pictures are mounted in shadow box-type frames and hung as household decorations. By the early postwar period, only one master blacksmith, Chu Yanquing, and a handful of his apprentices were active in the medium (Messerschmidt 2014). Following the Communist Revolution, the Chinese government collectivized the tiehua industry. The resulting state-owned monopoly, Wuhu Tiehua, brought artisans together in a large factory setting. For the next three decades, mass-produced tiehua pieces were sold in Japan, Hong Kong, and Southeast Asia; at its height in the 1980s, Wuhu Tiehua employed over six hundred specialized workers (designers, apprentices, skilled workers, and polishers) and employees performing support services (cleaners, cooks, physicians and nurses, etc.) in five machine-furnished workshops (Li et al. 2015).

In almost all respects, Wuhu Tiehua was a textbook monopoly firm. It was, of course, the only firm producing tiehua pieces in any meaningful volume, and as such, it enjoyed an unusually high degree of direct pricing power and abnormally high margins and profits, barring government price controls (Gao 2015). Although economic theory dictates that the pricing power of monopoly firms results in sizable welfare or deadweight loss in a market, the existence of Wuhu Tiehua arguably allowed for the exploitation of economies of scale—the ability to produce more at a lower cost per piece. Indeed, a common reason that monopolies exist is that they can decrease costs at most levels of production (Landsburg 2013). In the case of tiehua, having all the artisans under one roof created opportunities for specialization; as previously noted, the tiehua production process involved designers, fabricators, and finishers. Moreover, Wuhu Tiehua was able to produce tiehua pieces on a scale that was previously impossible, creating massive, wall-covering pieces of art that still adorn Chinese museums and government buildings to this day (see Figures 3 and 4). Pieces of such magnitude played a crucial role in placing tiehua on China’s cultural heritage map, making it a national—as opposed to regional—art form.

Members of today’s tiehua community suggest that the existence of Wuhu Tiehua may have also facilitated the modernization of tiehua production. Namely, veteran artisans point to the introduction of electric spot welding equipment as a radical transformation in the way tiehua is produced (Li et al. 2015). This, however, is a dubious assertion, as spot welding technology and techniques were developed in the late nineteenth century (Kou 2002), and this technology was adapted for use in tiehua production in the early 1960s. It is very possible—nay, likely—that private, competitive firms would have had the wherewithal to adapt such technology themselves and to perhaps do so even sooner than Wuhu Tiehua did.

Basic economic theory argues that monopoly firms tend to become less productive, as they do not face the market forces that incentivize competitive firms to innovate or provide better service. At Wuhu Tiehua, this manifested itself in the production of only traditional landscapes and bird-and-flower pieces for most of its history. While it is important in making this argument to balance consideration of innovation with consideration of tradition, we can look ahead and note that once the tiehua market became more competitive, the subject matter of tiehua pieces widened considerably (Ye 2015). Indeed, this is one of the largest differences that can be observed in comparison with the tiehua market today.

4. Reorganization and Privatization

4.1. Wuhu Tiehua

Under the rule of Premier Deng Xiaoping in the late 1980s and early 1990s, the Chinese government began to loosen its hold on the economy. As noted, economic reform was a gradual process, with the state slowly relinquishing control over factories and businesses. The tiehua industry was no exception to this broader trend. Although Wuhu Tiehua remained in existence, it saw a rapid decline in business, and in 1992, it initiated an aggressive cost-saving program that included wage cuts and outright layoffs. And the new tiehua entrepreneurs and their employees were quickly joined by colleagues leaving Wuhu Tiehua of their own volition in the face of declining compensation (Chu, Chu, and Li 2015). At Wuhu Tiehua, a second restructuring occurred in 2002, which released part of its ownership to its employees via private equity. Wuhu Tiehua remained in financial distress and formally declared bankruptcy in 2013. Today, Wuhu Tiehua is a faint shadow of its former self, employing fewer than ten employees—down from a workforce of six hundred in its heyday—in a dilapidated factory that appears almost abandoned and empty.

4.2. Spinoffs and Entry

As Wuhu Tiehua struggled with deregulation, artisans began to break away from the large firm to start their own companies. Not surprisingly, there have been growing pains associated with the many small firms now competing in markets where there used to be a single firm. Those that broke away from Wuhu Tiehua gave up total employment and life security: workers in state-owned factories in Communist China enjoyed numerous welfare benefits—informally known as the “iron rice bowl”—including free health insurance, housing, education, job security, and secured pension plans; all these benefits were lost after the economic reforms. Artisans faced the daunting task of also becoming entrepreneurs and managers, with little or no training or experience. In a competitive market environment, critical aspects of running a business, such as material acquisition and application, labor and salary dynamics, and pricing and marketing, were skills that needed to be acquired quickly lest firms fail. The tiehua market naturally experienced these transitional struggles. Not all the firms that currently operate have been very successful; some have done very well, while a few earn only a small profit. As is the case in entrepreneurship, however, there are rewards as well as risks: in addition to financial potential, these new artisan-entrepreneurs have expanded product lines and enjoy more creative freedom.

Following Wuhu Tiehua’s first restructuring in 1992, several laid-off workers founded Flying Dragon Tiehua. Flying Dragon recruited skillful masters and experienced designers and employed young marketing specialists for their sales (Gao 2015). Flying Dragon has become a leader in incorporating tiehua into practical everyday items, such as lamp shades and candle holders. Interestingly, another early entrant in the new tiehua market was Chu Family Tiehua, founded by Chu Jinxia, daughter of one of the original masters at Wuhu Tiehua, Chu Yanquing, after the 2002 factory restructuring (Chu et al. 2015). Continuing the work of her father, Chu’s firm specializes in high-quality, upscale pieces with traditional themes and is presently seen as one of the more successful new tiehua enterprises. Chu has since opened a second company, employing her two nephews, to create pieces that appeal to a lower-end, more popular market. The nephews report substantial sales growth and expansion plans (Huang et al. 2015). Today, there are eight tiehua firms in the market, including the Wuhu Tiehua remnant.

Orthodox economic theory argues that, in general, a free market is the most efficient way to allocate resources. The profit motive—and the realistic possibility of failure—will lead to greater innovation and superior quality of product as firms compete for customers, while consumers will have more access to the products they want at competitive prices. As the market expands, more firms will enter, creating jobs and increasing income. As such, the shift from state monopoly to a more competitive market system, as in the case of tiehua, should ultimately lead to a larger, healthier, and more efficient industry. Evidence suggests that this has indeed been the case in tiehua. There are certainly more firms, and the scope of industry product lines and subject matter has undoubtedly increased. Recently, for example, tiehua pieces featuring subjects as diverse as Jesus Christ, the Chinese zodiac, and western-style nudes have been produced, and some artisans are experimenting with styles that result in pieces bearing only a passing resemblance to traditional tiehua. Quality is another dimension that distinguishes tiehua pieces. The detail of a piece of artwork and the skill with which it was created is something that even a novice can recognize and appreciate, particularly in the more expensive pieces. The firms that focus more on these top-of-the line products used quality as their primary mode of differentiation (Chu et al. 2015). Other firms, as noted, produce cheaper and more practical works. In one way or another, nearly every firm will argue that it fills a unique niche in a growing market (Dan and Li 2015).

Almost every firm owner and their workers strongly believe they are better off since leaving the state firm, citing more creative freedom, higher pay, lower costs, and a higher quality of life. Managers and workers are almost uniformly emphatic in their optimism about future prospects. Likewise, artisans agree that the quality of the art they produce has increased since privatization, and they are able to produce a greater variety and volume of pieces, at lower per-unit costs. Despite the challenges of facing greater market competition and less than concrete job security, it is generally agreed upon that the free-market system has greatly benefitted the tiehua industry, exactly as economic theory predicts.

5. Going Forward

Although most members of the present tiehua community are of the opinion their industry is in good health and its future prospects are sound, the art form and its market face some challenges going forward. Chief among these is an issue notorious in Chinese business: intellectual property rights, or a lack thereof. This is especially noteworthy in tiehua, where innovation in subject matter and technique is so important to many firms’ market positions. This concern is exacerbated as tiehua pieces become cheaper and easier to produce, as it makes it easier for other artists and designers to steal ideas. Given that tiehua production workers are often hired on a short-term basis, it is very easy for an individual worker to join a firm, produce a piece of art, and leave, taking the ideas he or she has learned to the open market (Huang et al., 2015). The well-known lack of intellectual property protection in China threatens to stifle innovation in the tiehua market. In fact, tiehua artisans report that their works are frequently copied, sometimes within a matter of days (Huang et al. 2015). Economic theory argues that a breakdown of property rights is a source of potential market failure, and thus it will be of great interest to see how the tiehua industry—not to mention the overall Chinese economy—responds to this concern in the future.

Another ongoing challenge for tiehua producers has been the recent decline in the gift market. Dating to imperial times, formal gift giving is a very important cultural tradition in China; it is a way to demonstrate wealth and power. tiehua has historically been heavily intertwined with the gift market. In the past, the government was a huge customer of the high-end firms, purchasing very expensive pieces to present as gifts. The dark side of this tradition is that gift-giving regularly goes hand in hand with bribery, a well-known problem in China (Wedeman 2013). As the government in China has made an effort in recent years to eliminate corruption, laws have been passed to mitigate these types of “gifts,” to the detriment of many tiehua firms. As a result, many firms are looking for new sources of revenue, most often by expanding their product lines to include lower value-added products that the typical Chinese consumer can afford (Gao 2015). Not surprisingly, maintaining a balance between quality and affordability is an increasing issue for most new tiehua producers.

Lastly, there is the uniquely Asian issue of balancing profit and tradition. Tiehua artisans report a deep cultural responsibility to be good stewards of this ancient art form. Tiehua is often a family vocation, and workers and managers alike want to carry on that tradition in the best way possible. A large source of this sense of responsibility lies in filial and ancestral cultural traditions. That sentiment is alive and well in the tiehua industry. At present, this is most clearly seen in a sort of competitive camaraderie within the tiehua community; masters and business owners alike tend to encourage each other to do well and advance the tiehua industry as a whole (Ye 2015). It is clear that the continued practice and success of the tiehua art form is a high priority for every player in the tiehua industry. It remains to be seen how strong this sentiment will be as this market becomes more competitive and if the Chinese economy experiences more meaningful business cycles in the future (as previously noted, mainland China has not experienced a recession since the 1970s).

6. Conclusion

The tiehua market represents an excellent case study in market economics and Chinese economic development since the 1990s. As economic theory predicts, Wuhu Tiehua, the state-owned monopoly, faced few incentives to innovate and to become more efficient, as evidenced by the rapidity at which it floundered when exposed to market forces. Yet the existence of profit opportunities invited entry into the market, and Wuhu Tiehua has now been largely supplanted by several smaller, more aggressively entrepreneurial firms—again, exactly what economic theory would predict. Although few, if any, new tiehua entrepreneurs had meaningful business training and experience, they appear to have adapted to their new competitive reality quite quickly. And in the short run, we can expect new firms to continue to enter the market as long as continued profits are evident.

Today, tiehua is a generally sound industry, a mostly private market with several independent firms operating and able to earn reasonable profits. It is fair to say that as a result of privatization, the tiehua industry and its firms are better off despite the challenge of greater market competition and less-than-concrete job security. Under state ownership, factories were held to strict production standards with little room for individual creativity or exploration of different or new markets. As factories transitioned to private ownership, tiehua masters (re)gained control of production and were much more motivated to develop new techniques, broaden their markets, and expand their creativity. As tiehua firm owners, artisans, and workers realized that the time and work they invested would be directly related to their own success or failure, incentives were better aligned with effort. As a result of a more productive and successful industry, individual tiehua owners and workers have seen increases in their disposable income and greater personal freedom.

Looking beyond tiehua, it is reasonable to expect that the experience of tiehua has been and is consistent with that of other similarly sized industries. While further work is needed to better quantify the effects of privatization on the tiehua market, the results of this qualitative research bode well for the long-run vitality of small- and medium-size Chinese enterprises.

Appendix: Research Methodology

This paper is the result of a student-faculty research trip to Wuhu, China, in the summer of 2015. Our research consisted of interviews of various owners of tiehua firms, as well as their workers, with the goal of documenting how the industry as a whole has been affected by the transition from a planned to a private economy, how the artwork and pieces produced have evolved, and how the lives of those involved in the industry have changed in the new market setting.

Notes

- The authors would like to dedicate this paper to the memory of Peter Chen (1967–2021), whose expertise, patience, and good humor made this research much easier and considerably more pleasant. [^]

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

References

Atherton, Andrew, and Alex Newman. 2017. “The Emergence of the Private Entrepreneur in Reform Era China: Re-birth of an Earlier Tradition, or a More Recent Product of Development and Change?” Business History 58, no. 3: 319–44. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/00076791.2015.1122702

Chu Jinxia, Chu Tieyi, and Li Qing. 2015. Personal interviews at Chu Family Tiehua, June 2015.

Coricelli, Fabrizio, and Elena Ianchovichina. 2004. “Managing Volatility in Transition Economies: The Experience of the Central and Eastern European Countries.” CEPR Discussion Paper #4413. https://ssrn.com/abstract=560342.

Dan, Wenxiang, and Li Jun. 2015. Personal interviews at Huiyifang Tiehua, June 2015.

Gao, Wenqing. 2015. Personal interview at Flying Dragon Tiehua, June 2015.

Haveman, Heather A., Nan Jia, Jing Shi, and Yongxiang Wang. 2017. “The Dynamics of Political Embeddedness in China.” Administrative Science Quarterly 62, no. 1: 67–104. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1177/0001839216657311

Hsieh, Chang-Tai, and Zheng Song. 2015. “Grasp the Large, Let Go of the Small: The Transformation of the State Sector in China.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 45:295–346. DOI: http://doi.org/10.3386/w21006

Huang, Diajiang, Wen Dian, and Xing Houfan. 2015. Personal interviews, June 2015.

Knowledge at Wharton. 2006. “The Long and Winding Road to Privatization in China.” Knowledge at Wharton, May 10, 2006. https://knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu/article/the-long-and-winding-road-to-privatization-in-china/.

Kou, Sindo. 2002. Welding Metallurgy. 2nd ed. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1002/0471434027

Landsburg, Steven E. 2013. Price Theory and Applications. 9th ed. Boston: Cengage.

Li, Aiping, Shen Tao, Tang Chuangsong, and Wang Xiaolin. 2015. Personal interviews at Wuhu Tiehua Factory, June 2015.

McMillan, John, and Barry Naughton. 1992. “How to Reform a Planned Economy: Lessons from China.” Oxford Review of Economic Policy 8, no. 1: 130–43. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/oxrep/8.1.130

Messerschmidt, Lydia. 2014. “Wuhu Iron Paintings: Basic Research and Conservation of a Four-Sided Lantern.” Studies in Conservation 59, Supplement 1: s111–s114. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1179/204705814X13975704318434

Palepu, Krishna G., Tarun Khanna, and Ingrid Vargas. 2005. “Haier: Taking a Chinese Company Global.” Harvard Business School Case 706–401, October 2005 (revised August 2006.)

Walder, Andrew G. 1995. “Local Governments as Industrial Firms: An Organizational Analysis of China’s Transitional Economy.” American Journal of Sociology 101, no. 2: 263–301. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1086/230725

Walder, Andrew G. 1998. “The County Government as an Industrial Corporation.” In Zouping in Transition, pp. 62–85.

Wedeman, Andrew. 2013. “The Dark Side of Business with Chinese Characteristics.” Social Research 80, no. 4: 1213–36. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1353/sor.2013.0049

Ye, He. 2015. Personal interview at Wendian Tiehua, June 2015.

Zafar, Ali. 2010. “Learning from the Chinese Miracle: Development Lessons for Sub-Saharan Africa.” World Bank Policy Research Working Paper no. 5216. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1596/1813-9450-5216